The NSA’s newly released Guidance for Managing UEFI Secure Boot signals a long-overdue but critical shift: firmware-level security is no longer a footnote in cybersecurity policy; it’s front and center. For those of us who’ve spent years addressing firmware risks across the enterprise, the guidance is welcome and timely, as malware that bypasses Secure Boot has grown increasingly common. The NSA’s guidance adds visibility and credibility to an issue that is reaching a tipping point in urgency.

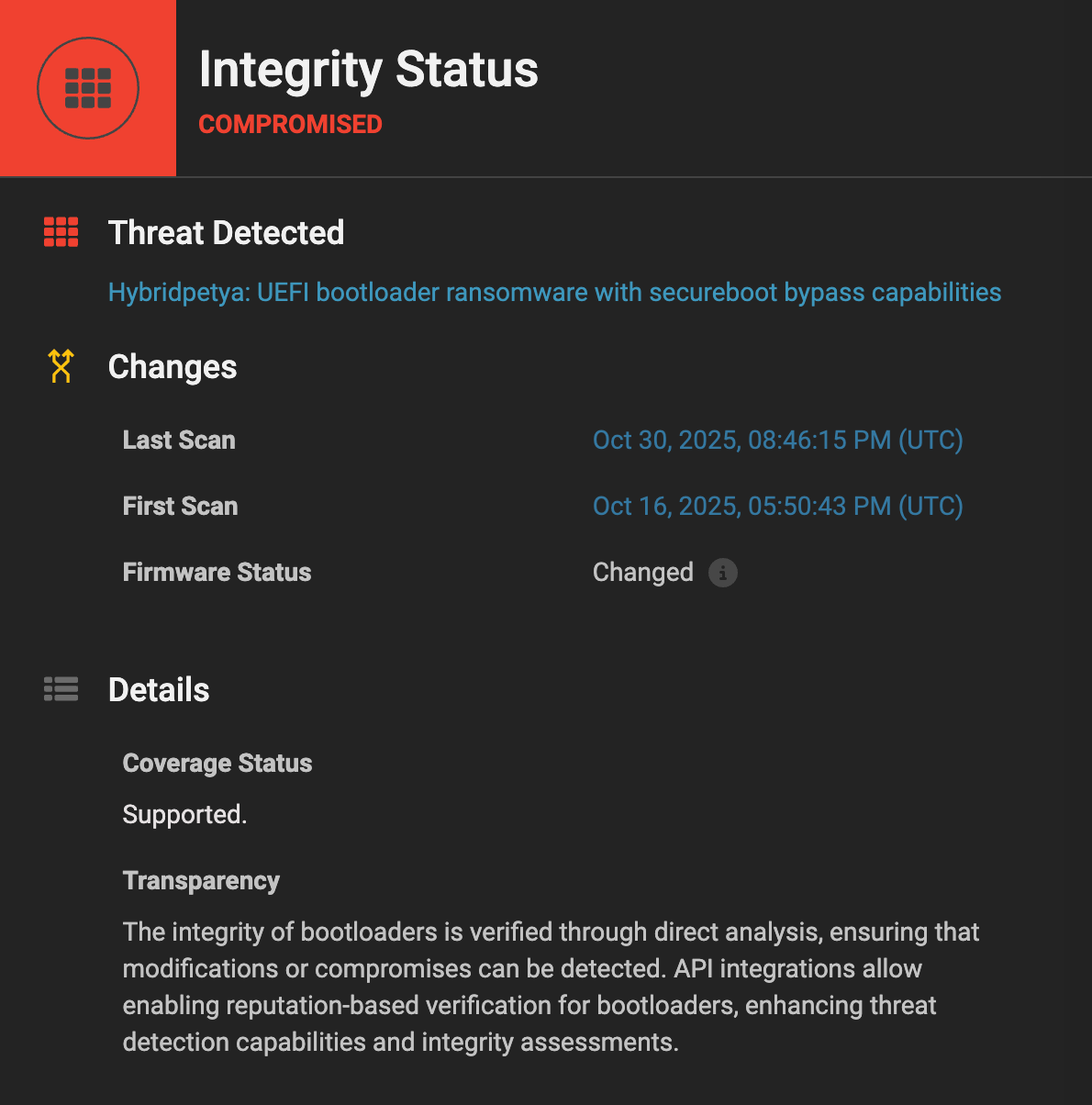

The NSA’s message is spot-on and very clear: If you’re not actively managing and validating UEFI Secure Boot configurations across your fleet, you are exposing your organization to persistent, invisible threats that traditional security controls will never detect. Their guidance identifies multiple threat classes, including PKFail, BlackLotus, and BootHole, that demonstrate the systemic failures that occur when Secure Boot is misconfigured or assumed to function by default. More recent and relevant examples that didn’t get a shoutout in the guidance include the Secure Boot bypassing HybridPetya ransomware, and the signed UEFI shell, dubbed Bombshell, that ships with many Framework laptops. This isn’t theoretical. These are live threat vectors, some already exploited in the wild, and increasingly trivial to deploy.

The Real Problem Is Operational, Not Technical

Secure Boot has been part of the UEFI spec since 2006. And yet the vast majority of enterprise environments still operate under outdated or default configurations, or worse, with Secure Boot entirely disabled. Why? Secure Boot remains operationally opaque for most IT and security teams.

As NSA highlights, many systems still use expired 2011 certificates, lack meaningful revocation (DBX) entries, or even ship with test keys that allow trivial subversion of the root of trust. Worse yet, critical firmware variables like Platform Key (PK), Key Exchange Key (KEK), and the allow/deny DBs (DB and DBX) are often misunderstood and mismanaged. These aren’t obscure missteps; they are enterprise-wide exposures.

We’ve seen this firsthand. Eclypsium research has repeatedly identified improperly signed firmware, exploitable bootloaders, and malicious persistence implants that survive re-imaging, evade EDR, and silently reassert control from below the OS.

NSA’s Advice Is Necessary. But Not Sufficient.

The guidance is practical as it outlines how to query Secure Boot status using native tools (PowerShell, mokutil, efi-readvar), and what a healthy PK/KEK/DB/DBX configuration should look like. It even addresses confusion around TPMs and BitLocker, clearly stating that these features do not imply Secure Boot is enabled or functioning.

But that’s not enough.

The document correctly states that Secure Boot is a local enforcement mechanism. What it doesn’t address is how organizations are supposed to operationalize this at scale. How do you inventory, validate, and continuously monitor these settings across thousands of systems, many built by different OEMs, with custom firmware stacks, variable bootloaders, and inconsistent update mechanisms?

This is where most organizations struggle, and where solutions like Eclypsium can help.

The Future of Secure Boot Must Be Continuous, Scalable, and Verified

Secure Boot only works if it’s configured correctly and remains in a known-good state. As we’ve said before, firmware is not static. It is updated (often silently) through vendor tools, OS updates, or even threat actor implants. And those updates may introduce new trust anchors, overwrite DB entries, or disable enforcement altogether.

An outdated DBX remains one of the most common misconfigurations detected today. Updating the DBX revocation list is essential, as signed software, such as bootloaders, may contain known exploitable vulnerabilities that allow attackers to bypass the Secure Boot root of trust. To make matters worse, the DBX is typically not automatically updated, and few tools can identify these conditions.

This is why we built Eclypsium: to deliver continuous visibility into the firmware and boot integrity of every device, PCs, servers, network appliances, and cloud infrastructure. We automatically extract, analyze, and verify the entire firmware stack, including UEFI, revocation lists (e.g, Secure Boot DBX), bootloaders, option ROMs, BMCs, and more, against known-good baselines, signatures, and behavioral models.

Without this visibility, the NSA’s guidance becomes yet another best practice that can’t be measured, enforced, or validated at scale.

Bottom Line

NSA’s guidance is a critical step forward, and it should prompt every CISO and security leader to ask:

- Do we know that Secure Boot is correctly configured across our fleet?

- Are we auditing firmware for implants and misconfigurations?

- Can we detect if our devices have vulnerabilities—before ransomware or nation-state actors exploit them?

If the answer is no, it’s time to act. Because, as the guidance makes clear, Secure Boot misconfigurations are not rare edge cases—they are attack surfaces. And in today’s threat environment, attackers are already there.

To see a demo of the Eclypsium platform’s capabilities in detecting Secure Boot configuration issues and related malware, IOCs, etc, please get in touch.

Related Resources:

Blogs:

- Enhanced Threat Detection: Bootloaders, Bootkits, and Secure Boot

- Microsoft Issues Patches for 24 New Secure Boot Vulnerabilities

- The Keys to the Kingdom and the Intel Boot Process

Videos:

- BlackLotus – How UEFI Secure Boot Became a Gateway for Cyber Attacks

- BlackLotus UEFI Bootkit Patching & Mitigations

Research: