Summary Take-Aways Up Front

While the media and industry is telling you that the hybrid/cyber conflict surrounding the invasion of Ukraine has been underwhelming, nothing could be further from the truth. The implications for our critical infrastructure and national security are immensely important. The wipers and destructive malware that have averaged a new variant/campaign once per week for the last 7-8 weeks make one thing clear: The actors have had persistence long before the destructive payload is launched, and the timing of each attack substantiates a primary take-away: Destructive payloads are not meant to win a game of chess, attrition or fatigue. (that’s what spyware, DDOS and DisInfo are for). Rather, they are reserved for use at a critical moment when the desired impact of the payload outweighs the benefit of persistence the attacker has enjoyed prior. The precise same actors behind NotPetya are well-positioned, motivated and capable of deploying a destructive campaign (Means, Opportunity and Motive firmly in place). Only now, a) the stakes are the highest they have ever been, b) the means to destroy devices at the motherboard or flash memory level are in place (and being exhibited in the wild) and c) the threat is exasperated because such means are now also in the hands of Pro-Russian hacktivists, who may not use as much discretion. The good news is, we can absolutely get much further ahead in our defenses by focusing on those threats that stand to do the most harm to our missions, safety, and operations, and prioritizing them accordingly.

INTRODUCTION

By now most readers are simply trying to keep and make sense of everything that has occurred in the cyber realm these last few months. This threat report will focus only on the most important, and especially those related to the invasion of Ukraine, and in particular those things related to low-level and destructive/disruptive impacts. The volume and diversity of cyber events surrounding the invasion of Ukraine is unparalleled in modern history. If it has an IP address, it’s been attacked. DDOS, Defacements, Ransomware, Wipers, en masse Doxxing, communications channels, satellites, reactor cooling management interfaces, weapons systems, infrastructure, mobile apps, devices, cameras…all of it. The cyber element of this hybrid war has spread to many dozens of countries, and has blurred all lines in terms of state-backed, criminal, and hacktivist actors. The implications for cyber leaders everywhere are more important than the cynical headlines claiming Russia’s cyber tactics have so far been ineffective: There is a marked difference in motives related to attacking a neighboring-country’s infrastructure that you intend to occupy (whose infrastructure you intend to re-use), and those related to attacking an enemy afar.

DISINFORMATION CAMPAIGNS SET THE STAGE

There’s simply too much to convey in a single report, so we will use images and screenshots to tell a story that has to be ‘seen’ to get a sense of the magnitude of such attacks related to the Ukraine conflict. We’ll start by painting a landscape where there are no rules, and where truth is hard to come by. A defining aspect of the cyber conflict has been disinformation campaigns. Here we have two images of Zelensky, can you tell which one is fake?

Russian hackers were hoping that no one could when they implanted a video on a Ukrainian news station. The real Zelensky would not ask his people to lay down arms, but the deepfake one that aired, did. Similar plots have unfolded, including elaborate Russian government attempts at sending hacked or spoofed emails from an Ukrainian embassy account that led up to interviews attempting to siphon information about naval vessel movements and nuclear weapons. Or more recently, a Russian-operated botfarm sent thousands of sms messages to Ukrainian military and police urging them to attack their own city of Kiev:

“The outcome of events is predetermined! Be prudent and refuse to support nationalism and discredited leaders of the country who have already fled the capital!!!”

While these (and dozens more) disinformation attacks may have varying degrees of impact, they serve as both real and symbolic reminders of what war-time cyber conflict looks like. The cyber “fog of war” has never been thicker.

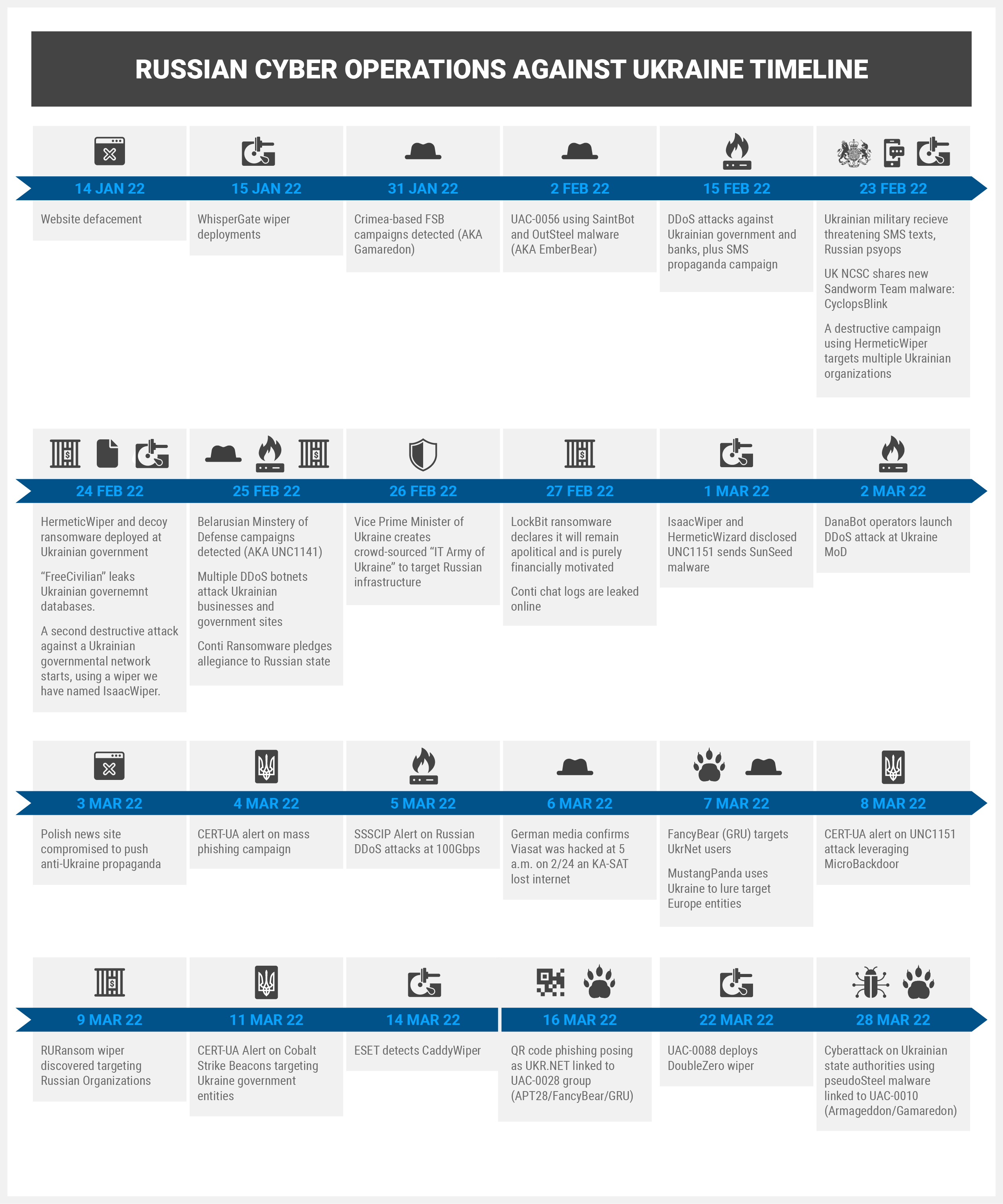

TIMELINE OF MAJOR CYBER EVENTS DURING INVASION OF UKRAINE

The following timeline depicts the order of cyber-related events as they have unfolded in the conflict:

THE WIPERS DEFINE THE CYBER CONFLICT

What the reader will notice is a large diversity of attacks that are destructive, disruptive and damaging to truth (aka “DisInfo”), or infrastructure, in various ways. While unsurprising, it should be pointed out that a half dozen of them take the form of distinct low-level ‘wipers’ designed to significantly damage the computing asset and its role in supporting a given organization’s mission or business. A secondary motive for use of wipers may be to stall or prevent forensic attribution efforts on the part of victim organizations. Taken together, however, these wipers represent what happens when threat actors turn to lower-level attacks designed to do more harm than run-of-the-mill ransomware, disinfo, website defacements or the all-too-common DDOS attacks. Some, like WhisperGate, may even be an (ultimately ineffective) attempt to false-flag (point a finger at) who the attacking party is in order to leverage the headlines for their socio-political gain. In this case Russian GRU’s UNC2598 group attempted to make the attacking party look like Ukraine itself, using the Trident logo, a ‘fake ransom’ BTC address that had already been used several years prior (and two of the same email addresses) and inferences that the wiper operation is associated with the Special Operations Forces of the Armed Forces of Ukraine. WhisperGate shares code with an earlier wiper, WhiteBlackCrypt, and WhisperGate’s MBR wiper component matches it 80%. This same Russian actor group also goes by the moniker “Free Civilian”, and uses commodity spear-phishing/malware to gain initial access. It has dumped (leaked) sensitive data for Ukraine targets as well as performed website defacements for purposes of misinformation and propaganda. This group has been tied to Russian GRU operations with moderate confidence. It is not, at this time, tied to either of the two most-commonly recognized Russian GRU actors; Sandworm, or APT28, and may even have dotted-line ties to criminal malware activity. Want the hot-take? While similar to NotPetya (targets MBR, acts like ransomware (but isn’t) and tied to Russian GRU operations), there are are two key differentiators: 1) It is deployed via commodity spear-phishing tools by a group that overlaps with criminal activities, and 2) It does more than only target the MBR, it also has a 2nd stage wiper that destroys files, too.

On the heels of WhisperGate came HermeticWiper, hitting targets in Ukraine, Lithuania and Latvia. Ukrainian targets included the Ukrainian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Cabinet of Ministers, and Rada (The Ukrainian Parliament). It stood out for targeting both the MBR (Master Boot Record) like NotPetya did, but also targeting disk partitions, OS files and the backup shadow copy. With a compile time months prior to the invasion and first-observed sample in the wild and the attackers first having access to AD (Active Directory) there’s a good chance the campaign was long-planned and the timing of the wiper payload was chosen precisely by the attackers to be on the eve of the invasion. While some of the TTP’s were similar to WhisperGate, overall HermeticWiper is more sophisticated, and includes worm-like behavior to better distribute itself within the environment. It even deletes its own components to make after-the-fact forensic and attribution analysis more difficult.

HermeticWiper activity overlapped with another less sophisticated wiper, IsaacWiper, which, midway through its campaign, was updated with debugging enabled in order to troubleshoot failed payload attempts.

A few weeks later in early-mid March, an undisclosed number of Russian targets suffered a wiper attack in the form of RURansom, likely written by a single author also associated with crypto-mining malware. It checked to make sure the victim device was located in Russia and encrypted files with an unrecoverable key.

A week later came CaddyWiper. Effectively shellcode compiled down to a portable executable, this wiper targeted victims in Ukraine, and shares some tactics with Trickbot and Maze malware, discussed further below in context.

Finally, a wiper dubbed DoubleZero targeted Ukraine victims by wiping both system and non-system files and critical registry settings, rendering the device unusable.

Note that we’ve only just scratched the surface of what’s transpired, focusing only on wipers for now. In one week alone, the Ukrainian CERT team recorded 14 different actor groups and attacks, none of them insignificant.

CISA knew these wiper attacks were coming. We all did, right? If so then why aren’t we all patching for these 13 Russian-targeted vulns? Or the rest of these 700+ most commonly in-the-wild targeted vulnerabilities CISA have curated for us?

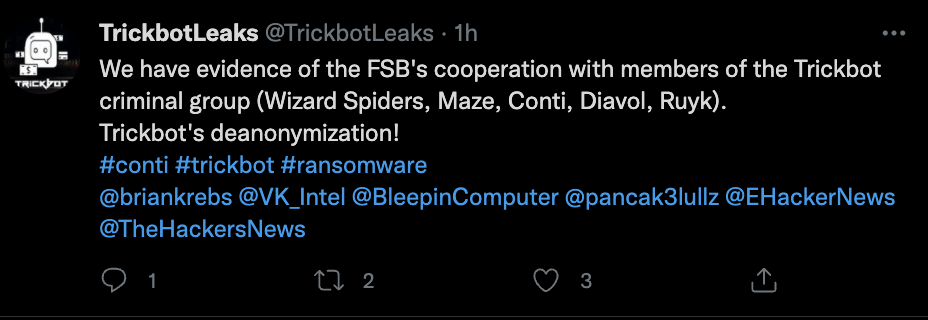

CONTI / TRICKBOT LEAKS EXPOSE FOCUS ON LOW-LEVEL AND DEVICE LEVEL ATTACKS

Earlier we mentioned Russian GRU UNC2598’s overlap with Russian cyber criminal activities. In similar fashion, nothing kept researchers more busy this month than the Conti/TrickBot leaks, leaked by a member that took exception to Conti’s public statement in support of Russia. From these leaks, some folks at Bellingcat, along with the group behind the TrickBot Leaks twitter account, have made a connection between certain Conti activities and the Russian FSB. Not good news considering Conti alone targeted over 60 ICS/Manufacturing targets recently. Also not good news considering the leaks show the same group testing the infamous PermaDll (aka TrickBoot) UEFI module working in their production bot environment.

Note that Maze is mentioned in this second reference alongside Trickbot/Conti. That is likely because there are affiliates, and there are code-overlap ties between the two just as there are code overlaps between both of them and CaddyWiper. All three also happen to know when they’ve landed on a domain controller (via the same “DsRoleGetPrimaryDomainInformation” method even), and choose not to harm the DC, presumably in order to be able to regain access again later and deploy additional payloads via GPO to the target environment. This tactic also infers that all three have likely enjoyed persistent access in the target environment well prior to dropping their respective payloads. Other than these loose connections, there is no formal attribution assigned to CaddyWiper as of time of this writing.

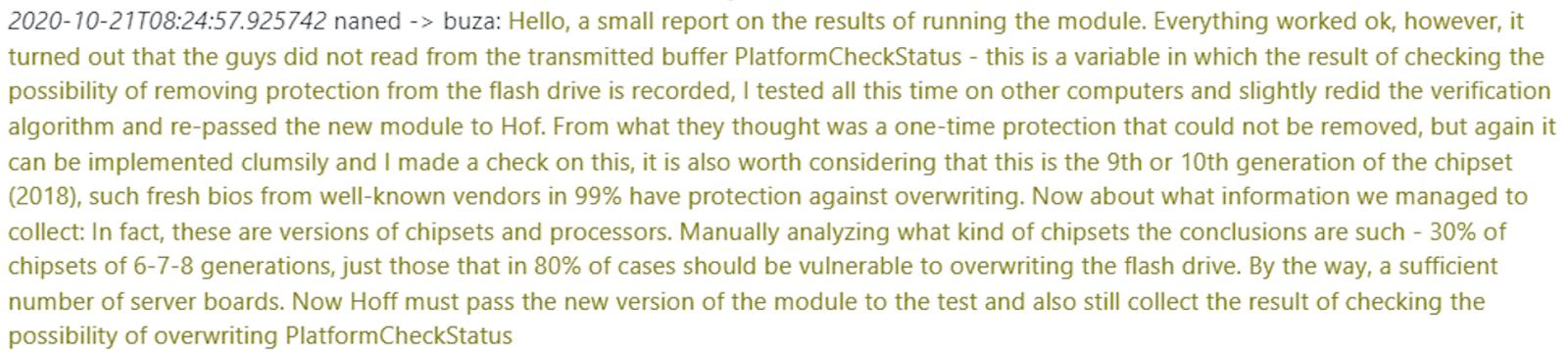

Pivoting back to the Conti and TrickBot leaks, they reveal the group’s efforts to develop low-level UEFI-based attacks in order to load malicious code prior to the primary OS and the security controls reliant upon the OS (AV/EDR/etc). Readers will recall our co-discovery of the TrickBoot module that looks for easily exploitable vulnerabilities at the UEFI level; but the leaks contain dialogue that extends more broadly to the advantage of low-level / bypass tactics in general. Affiliate developers were brought in to research and discuss such TTPs (Tools, Tactics and Procedures). One example would be in reference to this git repo, which is effectively a tactic that relies on encrypting an attacker’s executable with a custom password and hosting it anywhere on the internet such that nearly all local and Proxy AV-Protections and AMSI can be bypassed. Another would be the following conversation between “Buza”, and an affiliate developer “Naned” who claims after manually verifying, that 80% of the time an exploit will work against any Intel generation 6, 7, or 8 chipset, including server blade variants. They estimate 30% of target devices would fall into this category. This, from a criminal organization that was deploying up to 40,000 new infections daily around the same time. In particular tactics targeting the UEFI are highly valued as effective ways to bypass or subvert endpoint security controls on the target OS. This exchange took place only a month prior to the PermaDll (Trickboot module) discovery (Translated from Russian):

Perhaps the most telling, however, is an exchange between the boss “Stern”, and developer “Naned” in June of 2021, some eight months after the Trickboot module discovery. Recall that Trickboot looked for the BIOSWE (Bios Write Enable) vulnerability that LoJax and MossaicRegressor leveraged to write to the SPI flash. This well-known vulnerability is one that is often patched, and may or may not be found on the targeted system. Fast forward eight months, and Perhaps “Naned” wanted to explore other initial vulnerability vectors to the SPI flash; ones that might potentially be more universal in their targeting, and ones that might leverage less well-known vulnerabilities, like the Intel ME vulnerabilities discussed in the screenshot below:

Further research into this evolution of tactics would be worthwhile and something the Eclypsium team may take a closer look at.

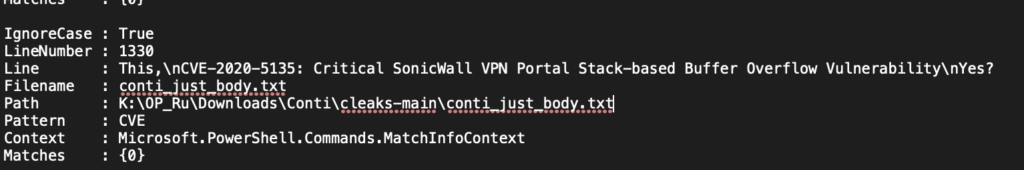

Beyond discussing methods that target the UEFI, AMT, and Intel ME, Conti also actively exploits vulnerabilities in externally-facing devices. Doing a search across several Conti/TrickBot data sets for the letters “CVE” was a worthwhile effort, returning over 3000 unique mentions of CVE’s in conversations between developers and affiliates. A pertinent example would be the SonicWall CVE-2020-5135 vulnerability.

SonicWall related CVE’s alone are mentioned/discussed dozens of times. There are also mentions of CVE’s related to Fortinet and other VPN devices, as well as a curious amount of discussion and research looking at how to transfer config files from one MikroTik device to another, a technique that paralleled our team’s own research observations when examining the Meris botnet activity last fall. These devices are mentioned several dozen times and links to their procurement (presumably for malware development and testing, etc.) are present in the leaks.

One more thing; The Conti/Trickbot Darwin Award goes to developer “Naned”, who managed to brick his own development box while building the same Trickboot module the Eclypsium team and Advanced Intelligence co-discovered only a month later. In a twist of poetic justice, Eclypsium researchers alluded to just how easy it is for an actor (with remote or local admin) to brick a box by changing just one line of code in the Trickboot module…note the timestamp; Naned did this to himself before the Trickboot discovery. So don’t take our word for how easy it is to do, nor how long it takes to recover a bricked device (10 days), take his:

And from our blog:

Additional context with a screenshot indicating “Naned” is a primary author of Trickboot here via @tyler_robinson and @pancak3lullz (unsung cyber heroes both). Of note is that “Buza” specifically asked “Naned” to develop a low-level vector like LoJax, a tool the Russian GRU have used for many years to persist indefinitely on the UEFI of implanted devices, and one Eclypsium researchers have written and spoken about for many years as a quintessential example an effective campaign targeting firmware.

Finally, if you ever wished you could sit down and analyze Conti’s latest contilocker source code, well, now you can.

DIVERSITY, MOTIVES AND SIZE OF CYBERWAR PARTICIPANTS

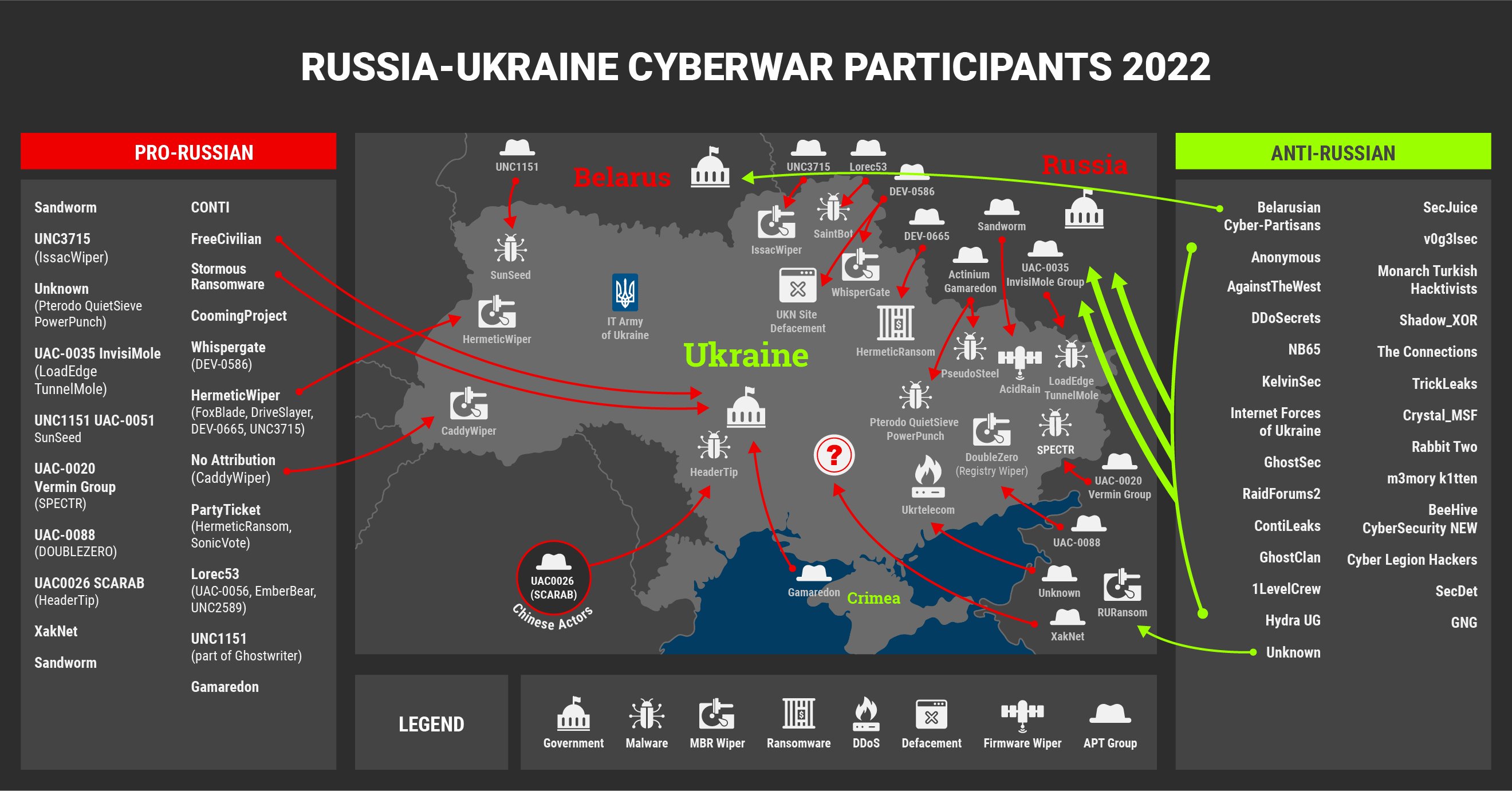

One of the most under-reported stories of the conflict is the sheer number of actors both for and against the invasion. The map below is fodder for a novel, let alone a threat report like this one, but we took painstaking time and effort to depict the types of threats, their actor affiliations when known and the multiple aliases many of them go by. At some point our graphic artist wasn’t comfortable with how visually crowded the map had become, at which point this author assured them that, indeed, this is the whole point: Let this picture paint a thousand words, and one of them is ‘mayhem’.

There are many threat actors that reside inside the borders of Ukraine. It is a relatively small community of both actors, cyber security professionals and researchers who mostly all know who each other are. Many of these relationships extend across the border to individuals living inside Russia. The net result is a semi-complex web of relationships now forced to take a side whether by free will or indirect/direct force. Some of them have had fates worse than others since the invasion began, including one who was lost inside Ukraine, who happened to be the primary author of a Russia-based malware named Racoon Stealer:

And this is just within Ukraine and Russia. As expected, actors around the world of all walks, nationalities and affiliations have taken sides at this point.

The map tells ‘the story so far’ but if this newsletter leaves the reader with one take-away, it should be that many of these same threat actors have added or will add Ukrainian/NATO allies to their list of targets. While we know that the Russian GRU, FSB and SVR are longstanding adversaries, we might soon need to contend with a similar level of intensity originating from hacktivists within the cyber-criminal world. A few days ago, a pro-Russian actor that goes by Killnet targeted an International Airport in Connecticut USA, leaving the words “when the supply of weapons to Ukraine stops, attacks on the information structure of your country will instantly stop”. Killnet has since been insta-doxxed on the DoomSec TG channel as Вова Дунаев, along with their email, pw’s and more. And so it goes, back and forth, multiplied by dozens of groups and rivalries, all motivated by the conflict in Ukraine.

Over the last year many dozens of threat actors have been arrested in Ukraine, including Egregor and many others responsible for hundreds of attacks on (mostly) US targets. Speaking of arrests, the US DOJ recently charged four Russian state actors with a multi-year long campaign that deeply penetrated US critical infrastructure, including oil and gas firms, nuclear power plants, utility, and power transmission companies. Both the Triton/HatMan and Havex malware strain operators were indicted. Of course, charging actors and actually apprehending and preventing them from further actions are two different things. This holds true for ransomware actors inside Russia as well, and as President Biden recently warned, we may soon be due for a deluge of ransomware.

“Overall, roughly 74% of ransomware revenue in 2021 — over $400 million worth […] — went to strains we can say are highly likely to be affiliated with Russia in some way. “ via ChainAnalysis. Open season may well be in the cards, despite Russia’s veiled attempt to appease America by arresting members of the Revil ransomware gang just prior to the invasion.

On the flip-side there has been a tremendous amount of hacktivism in support of Ukraine by various actors including many within the re-energized Anonymous collective. Everything inside Russia has become ‘fair game’ it would seem: The The Federal Service for Supervision of Communications, Information Technology and Mass Media, (aka Roskomnadzor, or just Russia’s centralized censorship arm), several Russian banks (central bank of Russia, etc), Defense and Aerospace Rostec, Rosatom (State Nuclear Energy Corporation), Transneft (the R&D department of Russia’s state-controlled pipeline company), Roskomnadzor (Russia’s primary censorship organization), RostProekt (a large construction/infra company) and many more leaks, that when combined, provide any would-be attacker with sufficient information on key Russian personnel, Intelligence (FSB, SVR, GRU) and elites, to target them effectively. Hotel chain databases, airline and license plate databases combine to great effect. One might describe the culmination of these leaks as Russia’s “OPM Breach” moment, only carried out by hacktivists instead, and leaked to the world instead of being held close to the chest. An example of intelligence analysis would be the IT Army of Ukraine’s dump of Yandex food delivery database, which was later tied to FSB agents’ delivery/food orders.

Internal (and extending well beyond) to Ukraine borders is the called-to-arms “IT Army” who have targeted several Russian banks, the Russian rail system and power grid, and have conducted widespread DDoS attacks on strategic targets.

ONE MORE THING (YET ANOTHER WIPER)

Finally, for those that don’t believe six wipers is nearly enough for one threat report, we have a seventh. This one takes the form of a wiper that affected the ViaSat satellite consumer broadband network by destroying modems on the ground via issued commands from the management network associated with those modems’ management.

Per VIASAT this was a chained attack beginning with the compromise of a “misconfigured” VPN device. From there the attacker moved to a management network and abused “legitimate” commands to overwrite memory on tens of thousands of modems, rendering them useless. Analysis performed by Reversemode explored the potential for attacking the modem firmware via management protocols, in particular the TR069 protocol, that can be used to upload and run arbitrary binaries on the modems:

“A deeper look at the ‘ut_app_execute_operation’ function revealed that it is implementing a functionality that enables the ACS to install (upload and run) arbitrary binaries on the modem, without requiring either a signature verification or a complete firmware upgrade. This functionality seems to match both the Viasat statement as well as the approach to deploy the ‘AcidRain’ wiper described by SentinelOne.”

And thus we learn the name of the newly-discovered wiper malware, “AcidRain”. Among other things what makes this wiper interesting in the context of the Russian invasion is that it shares a portion of code functionality with that of VPNFilter: both erase the mtd files via the MEMGETINFO, MEMUNLOCK, and MEMERASE IOCTLS. Researchers point out that AcidRain has sloppier code and is more ‘universal’ in nature (can be more easily aimed at other similar devices). While more research is needed to make the connection, it would at least be plausible to suggest the Russian GRU were in a hurry to develop a means to universally target this class of devices as a continuation of their overall VPNFilter, Cyclops Blink, and now AcidRain mission charters, and in support of the invasion of Ukraine. If you haven’t read up on Cyclops Blink yet, we highly recommend you do. It may just end up being one of Russia’s primary offensive cyber weapons once fully unveiled. Time and more research will tell.

The attack is also interesting given ViaSat’s description of the initial vector into the management network, gained by “an attacker exploiting a misconfiguration in a VPN appliance.” Was this via exploitation of an RCE (Remote Code Execution) in an unpatched firmware version (and hence the “misconfigured” device)? Was this a chained attack that went from user creds to an attack surface that would allow for exploitation of a firmware BIOS Write Enable bug (also an ‘exploitable misconfiguration’) akin to something like this? Was this simply a device that didn’t have MFA turned on as a policy? We won’t know until and unless further forensic details are revealed, but suffice it to say, the particular threat actor in question has a long history of targeting VPN and network infrastructure devices to great effect. Literally everything in this 2018 CISA Alert should be considered ‘in play’ for this class of device, to include ways an actor can “leverage this capability to overwrite files to modify the device configurations, or upload maliciously modified OS or firmware to enable persistence” via the SIET tool. The take-away for any low-level attack at the network layer here is simply this: not only does the attacker own the device and therefore the traffic, but they also gain a disruptive or possibly destructive capability they get to use at an arbitrary time in the future; when the resulting impact is more valuable than the persistence they’ve enjoyed prior. We must remember that certain elements of cyber warfare are less about attrition, and more about well-timed tactical surprise. This is why the day before NotPetya hit no-one saw it coming. This is why several of these latest wipers already have Active Directory level access prior to payloads hitting later on. Finally, this is why we haven’t read about an attack on US infrastructure resulting in major impact: it simply hasn’t been the right time, and hopefully never will be.

“The magnitude of Russia’s cyber capacity is fairly consequential and it’s coming” – President Biden

RECOMMENDATIONS FOR GOVERNMENT, CRITICAL INFRASTRUCTURE AND FINANCE ORGANIZATIONS

- Leverage the efforts, tools and alerts from CISA within your organization to proactively raise awareness, urgency and understanding of these low-level threats and how they would disrupt mission or critical operations, safety and uptime.

- Proactively monitor for any of these known heavily-exploited vulnerabilities that CISA curates for you as they obtain ground truth actionable DFIR intelligence from the field.

- Gain visibility into, and proactively manage mitigation or remediation of those threats that stand to cause the greatest harm to the organization or mission. (e.g. those low-level threats that lead to indefinite downtime, patient/worker safety impact, or cascade-type downstream supply-chain impacts)

- Proactively and continuously monitor and patch all externally-facing devices in the firewall/vpn category daily for changed configurations, user accounts, traffic emanating from, and “impossible traveler” type of authentication events. What looks like a stolen/purchased credential access attack, may also have been a remotely-exploited device prior.

- Gain visibility into, and proactively register enterprise/mission risk for low-level attacks targeting the UEFI/BIOS, BMC’s, HDD’s, and other firmware level vulnerabilities that modern criminal and nation state actors are focusing on and actively exploiting. Prioritized risk management of this category of vulnerabilities based on impact potential foremost. Quantify that impact against acceptable downtime, safety, and costs of remediation. Next, assess likelihood while factoring in potential threat actor profiles and their means, opportunity and motives. When possible, pull from MITRE ATT&CK to determine gaps in visibility, segmentation, detection, and playbook/response. This process should look different from assessing run-of-the-mill OS/application level vulnerabilities, given the potential for indefinite downtimes (e.g. impact scenarios for which neither OS backups nor spare hard-drives can provide restoration of operations)

- Proactively and continuously require remote workforce to update (patch) modem and home router devices, as well as common IOT devices, mobile devices, etc.

- Factor in recent high-profile breaches and source-code leaks stemming from attacks on Microsoft Bing, Microsoft Maps, Microsoft Cortana, Microsoft Azure (Security), Microsoft Exchange, Microsoft Intune, Globant, Nvidia, Samsung, Ubisoft and OKTA (via SITEL) by LAPSUS$ and the Russian SVR. Add to your threat model the notion that whether it is teenagers like LAPSUS$ or a foreign intelligence agency, that source code (and the vulnerabilities that are exposed within) are now in the domain of nearly any actor profile with any motive. That’s totally OK though because “[…] we do not rely on the secrecy of source code for the security of products, and our threat models assume that attackers have knowledge of source code. So viewing source code isn’t tied to elevation of risk.” -Microsoft Does this mean that the 95% of Bing source code now out in the wild doesn’t matter? If it doesn’t then why is this even news? Even the developer comments alone might be valuable to an attacker navigating the code for vulnerabilities. While seven members of LAPSUS$ have been arrested, the group is still active.

We here at Eclypsium like to end things on a positive note. Just as this report is about to go out, we have received news via Attorney General Garland that a global botnet of thousands of devices (read: The GRU’s CyclopsBlink botnet, confirmed) has been taken down:

It gets better, special agent Mike N. out of Pittsburg tells the ‘rest of the story’ on twitter:

And this wraps up this month’s Below the Surface Threat Report! Please do see our note at the bottom regarding a Free QuickScan Tool that allows organizations impacted by the invasion of Ukraine to detect low-level firmware and device level threats and vulnerabilities on their devices. This is where the rubber meets the road: take action to gauge the actual risk of the low-level destructive attack surface in your organization or mission. Remember, the stick of dynamite can be thrown in either direction. Call this FUD, or call this Common Sense: your choice.