Summary Take-Aways Up Front

- Russian threat actors continue to employ multiple IV (initial vectors) into target networks, and carry out multi-objective operations once inside, with the primary aim of either long term persistence, destruction, or both

- Russian actors, including a newly identified espionage campaign, are more and more turning to connected devices within an environment to maintain persistence, disrupt operations, evade security controls and exfil or tunnel information and C2

- VPN devices serve as a primary IV (initial vector) into enterprise and government networks

- CISA’s known exploited vulnerabilities list, including this top 15 list, is key in deterring all threat actors of significance

- Exploited vulnerabilities continue to serve as a primary vector into organizations

Let’s just call this what it is. The US (and NATO allies) are in a cyber war with Russia, fighting tooth and nail against both nation-state affiliated actors and criminal actors alike. The nature of this cyber war is one of continued, steady escalation, as well as diversification of TTPs observed in the wild. Stakes are getting higher, and with them come bolder moves from both sides of the cyber conflict. While the invasion of Ukraine forms a centerpiece of discussion and is itself a large impetus for this escalation, it does not encompass the breadth nor gravity of the broader cyber conflict. This conflict did not begin on the eve of Feb 23rd, nor will it ever end.

From our vantage point here at Eclypsium, given our expertise and pedigree in the area of low-level attacks on firmware, supply chain, drivers and devices, we see playing out exactly what we had feared would: Attackers of all ilk and motive, are turning more towards lower-level attack vectors, and for good reasons: they are able to evade the rest of the security stack, persist indefinitely, and reserve the option to disrupt or destroy critical assets at a time of their choosing.

Equally apparent, is that actors are further leveraging connected devices within enterprise and operational environments as a core part of their overall attack methodology. Both externally-facing devices like VPN appliances, but also, too, devices on the inside of networks in the form of routers, cameras, printers and other soho/IOT devices. These devices are providing similar low-level advantages for the attackers with some additional expanded benefits as well: Evasion, stealth, persistence, tunneling, exfiltration, disruption/destruction, credential theft, backdoors, diversion, and more.

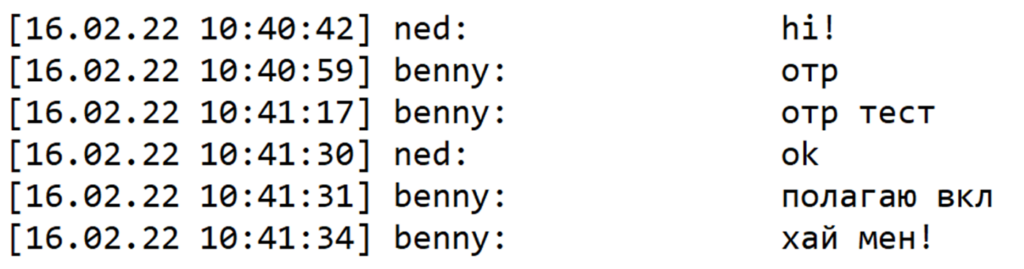

Recently there was (yet another) Trickbot group leak, only this time the chat logs leaked are from much more recent conversations earlier this spring. In these leaked chat conversations we are able to glean some more insights regarding the group’s use of such devices. Much akin to last month’s threat report we are fortunate to be able to lead off with some additional Darwinian humor; the beginning of a chat between “Ned” and “Benny”:

Which translates as follows:

Ned – hi

Benny – otr

Benny – otr test

Ned – ok

Benny – I think it is on.

Benny – Hi bro!

Ironically enough, indeed the chat client’s OTR (Off-The-Record) encryption was not enabled, else we wouldn’t be staring right at it. Hey Benny… “Hi Bro!”

Humor aside, in another chat between Beeny and Ruben, we see Benny asking questions about how their tooling around network devices works. One tool in particular, is called ‘checker.sh’:

Without translating every line, and extrapolating from additional pretext, we see that the checker.sh tool can be used to not only test for a vulnerability but also infect a device. It can ingest a list of routers to scan as one argument, or take another argument which will immediately infect them via a supplied list of C2 IPs. We see references to attacking MikroTik and Ubiquiti routers, and that an entire list of routers and dumped credentials is used. Looking at context prior to and after this section, one gets the idea that one part of the group finds the routers via a number of means, another group does the scanning of them, another develops the tooling, infects, credential dumping, and so on:

“Thank you man, I am awaiting material from a new seller, will be checking”. Here, ‘material’ likely refers to a user/password list that has been purchased, for example.

Taken as a whole, this latest Trickbot Leak confirms (and exposes first hand) what many analysts and DFIR heroes have long observed: that both Trickbot and Conti groups thrive on these types of devices, and have a very structured and effective layered approach to attacking them, whether on the internal network or whether they are externally-facing for initial access. Recall that after the Microsoft and US Cyber Command take-down attempts in 2020, Trickbot fell back to Mikrotik devices for their C2, as they were beyond the ‘reach’ of Microsoft’s legal arm, and beyond the rest of the security stack’s telemetry too. Over a year later, and they are still putting this class of device to effective use. These devices have become targets unto themselves, meaning it matters not who their owners are or the assets sitting behind them, as they have their own intrinsic value in providing tunneling and C2 for actors. Yet, indeed, a compromised router provides myriad vectors to attack devices behind it, and their communications to the Internet.

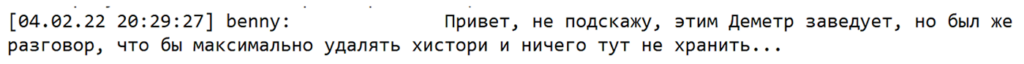

In a case of Darwinian double-irony, we’ll close this section with the following:

“Hi! Can’t say, Demetr is the one responsible for this, but there was a talk to delete history as much as possible and not store anything here…”

Looks like they goofed that one up, too. We’ll call this the “Benny Spill Show” for reference.

But of course it isn’t only Conti and Trickbot that leverage these devices. A new espionage threat actor, UNC3524 (possibly related to Russian GRU or SVR) relies on obscure devices in order to persist up to 18 months; 30 times longer than the 18-19 day dwell times seen in Conti infections. As Mandiant wrote in their research:

“For their long-haul remote access, UNC3524 opted to deploy QUIETEXIT on opaque network appliances within the victim environment; think backdoors on SAN arrays, load balancers, and wireless access point controllers.These kinds of devices don’t support antivirus or endpoint detection and response tools (EDRs), subsequently leaving the underlying operating systems to vendors to manage.”

They didn’t just stop there; they also deployed the server component of the QUIETEXIT tunneling malware on LifeSize and D-Link camera systems exposed to the internet that were running outdated firmware.

If you are asking yourself “how would I even detect this activity?”, you are not alone, and it’s exactly why such groups are operating nearly malware-less on the traditional x86 hosts, and doing more of the lift on the connected devices around them.

Such cameras have been exploited in the past, too. You’ll find IP Camera CVE’s like CVE-2020-5735 and CVE-2021-36260 present on CISA’s all-important list of Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (KEVs). And you’ll find vulns for other D-Link devices there (CVE-2015-2051, CVE-2021-42237 and CVE-2020-9377), and even an Ubiquity CVE too (CVE-2010-5330). And these are but a fraction of the 650+ known-exploited vulnerabilities CISA is urging you to address foremost. It’s why Eclypsium applies a tremendous amount of research into understanding how attackers discover, analyze and attack the firmware of such devices, so that organizations can understand their networks through the lens of real-world threat actors.

Just prior to publishing this report, news broke of a newly discovered bug (CVE-2022-1388) in F5 BIG-IP devices that allows an unauthenticated attacker to gain remote code execution on the system through bypassing F5’s iControl REST authentication in the management interface. It wasn’t more than a few minutes later that one of our own researchers witnessed an active attack take place on one of our test lab cloud instances we use to develop our solution. After doing preliminary analysis, the payload that was dropped looks to be none other than the BillGates botnet, the same payload that has also been dropped onto numerous devices vulnerable to the Log4Shell vulnerability. This, only 5 days after the CVE was published. Already many hundreds of devices have been exploited and many thousands remain vulnerable. Should there even be that manyf publicly facing management interfaces? Normally the answer would be a resounding ‘no’…but in these times, when even core IT staff work remotely, remotely-accessible interfaces are no longer an exception. As in every instance described throughout this newsletter, the things an attacker can do once they have taken full control over a critical device, are nearly unlimited in scope, and impact. Does this affect most organizations? Absolutely, F5 BIG-IP products are deployed in tens of thousands of companies, and heavily inside medical organizations worldwide.

These kinds of attacks are, across the board, the shortest path for an attacker to take, with the least amount of effort, the least chance of being detected and evading the endpoint-centric security stack, and what’s more, the fastest way to target critical assets on the internal network too. When asked to create a simple demonstration of just how fast this can be done, one of our researchers sent back a video he made of an attacker going from a shodan scan of vulnerable VPN devices, to an RCE exploitation of them via metasploit, to a shell that they used to target an internal Windows host, to root on that device, all in less time that it has taken you to read this month’s Below the Surface threat report.

This is precisely why CISA continues to curate and push out what is perhaps the single most important and actionable tool your organization can use, their list of Known Exploited Vulnerabilities (aka ‘KEV’s), including a ‘top-15’ list recently too. Their number one recommendation includes the patching of firmware as a top priority: “updating software, operating systems, applications, and firmware, with a prioritization on patching known exploited vulnerabilities; implementing a centralized patch management system; and replacing end-of-life software”

Once again a picture (courtesy of AdvIntel’s Andarial platform) is worth a thousand words. Here you see the VPN vector serving to provide initial access to some of the worst ransomware actors there are: Conti, Hive, REvil and LockBit.

So we’ll leave you with this last question:

If threat actors are successfully finding easy-to-exploit device firmware vulnerabilities, shouldn’t we be able to do the same inside our own networks? Shouldn’t we know what percentage of our environment is vulnerable to threats that aim to persist there indefinitely or cause the most destructive impact to mission, safety, or uptime? While rhetorical by design, this question should at the least, serve to enable a brass-tacks conversation with the right stake-holders.

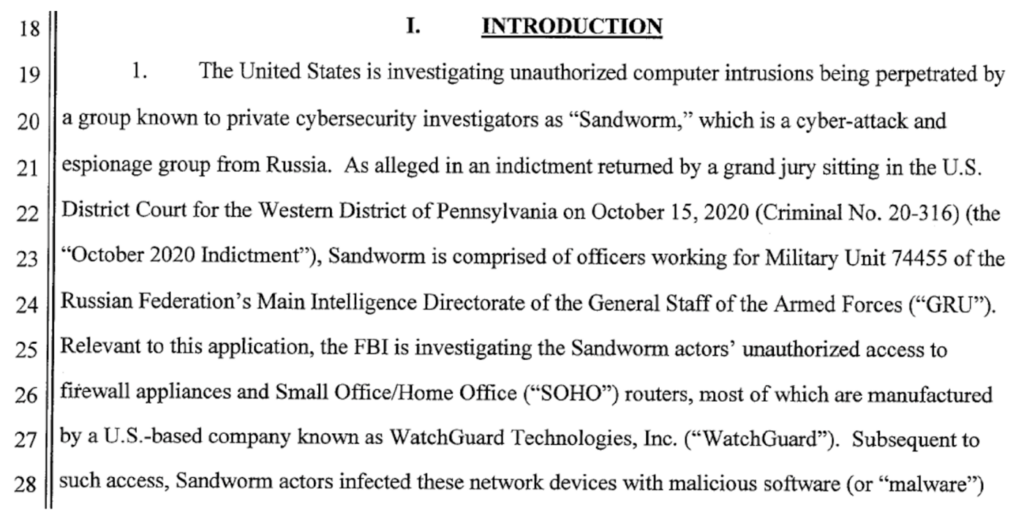

Finally, against the backdrop of this cyber war, the US Government is stepping up efforts to identify and indict both nation-state and criminal actors originating from Russia. Here, Sandworm (Russian GRU, Unit 74455) actors are called out for attacking SOHO routers.

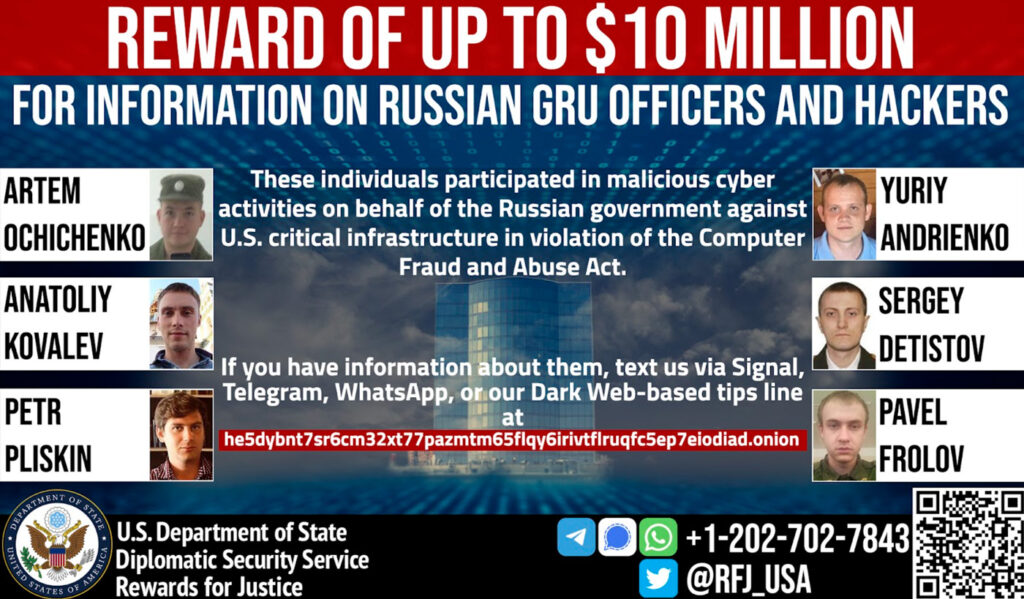

Next, there is a reward for information related to these and other activities. The anonymous tip hotline is here:

http://he5dybnt7sr6cm32xt77pazmtm65flqy6irivtflruqfc5ep7eiodiad.onion

And, sure enough, there is also a reward for members of Conti, which are now rumored to be so disrupted by the Conti Leaks and efforts of the community, that they may soon no longer remain as an holistic entity. Likely, they have already rebranded and will emerge again in some new form and method of operations and TTPs. The recently observed BazzarCall call-center social engineering campaign, for exampleBut for now, a tip of the hat to those who have worked behind the scenes to aid in their demise.

Speaking of infamous ransomware groups rebranding, it kind of flew under the radar, but suffice it to say, that REvil has resumed operations, after its core developer resurrected their infrastructure and a new encryptor sample was found in the wild to validate their return. This, despite two dozen arrests of their members just prior to the Ukraine invasion. Let’s hope this group hasn’t been ‘influenced’ by conversations with Russian intelligence officers during their brief time offline, now that Moscow has cut cyber-conviction related communications with the US.

So, we are back to where we began: the cyber war is real, ongoing, and always escalating. Let’s all hope for the best, and continue to work together as an industry and community, to defend against and bring down those that wish to harm us the most.