Secure Boot Matters

We cannot blindly trust software. The software (and firmware) we know and (sometimes) love today simply cannot be trusted without validation. Several recent examples of supply chain breaches such as xz utils, Sisense, Rust libraries and so many more are evidence enough that software cannot be trusted. While validating software supply chains is difficult, we have tools and techniques to can help mitigate the risk. UEFI Secure Boot is one such solution, allowing for the validation of firmware and software used in the boot process. Some will say “Secure boot is nothing more than snake oil” and others say Secure Boot was designed by lunatics. But we simply cannot dismiss Secure Boot and other technologies that allow us to have a higher degree of trust in the software we use every day.

All software has bugs and vulnerabilities and Secure Boot is no exception. This month, Microsoft gave us fixes for 24 new vulnerabilities in Secure Boot. That’s right, 24! I see this as a positive thing for the security community. While no software is perfect, fixing and patching is all we can do, and it’s far more dangerous not to patch something. I believe (okay, my opinion) that Microsoft is going all in on Secure Boot. They recently commissioned security researcher Bill Demerkapi to look at the security of shim, leading to the CVE-2023-40547 vulnerability discovery, and also announced upcoming updates to the Secure Boot certificates. This is all progress. For good measure, April’s Patch Tuesday not only fixed 24 Secure Boot vulnerabilities, but also addressed a Bitlocker bypass (CVE-2024-20665) and a Lenovo UEFI vulnerability (CVE-2024-23593).

The 24 Secure Boot vulnerabilities from April’s Patch Tuesday are listed below, along with the researchers credited with the discovery:

| ID | Type of Weakness | Max Severity | CVSS | Credit |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CVE-2024-20669 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 6.7 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-20688 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 7.1 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-20689 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 7.1 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-26168 | CWE-122: Heap-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 6.8 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-26171 | CWE-190: Integer Overflow or Wraparound | Important | 6.7 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-26175 | CWE-125: Out-of-bounds Read | Important | 7.8 | Azure YangMeir Bloya (Microsoft) |

| CVE-2024-26180 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-26189 | CWE-20: Improper Input Validation | Important | 8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-26194 | CWE-347: Improper Verification of Cryptographic Signature | Important | 7.4 | Microsoft |

| CVE-2024-26240 | CWE-20: Improper Input Validation | Important | 8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-26250 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 6.7 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-28896 | CWE-122: Heap-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 7.5 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-28897 | CWE-20: Improper Input Validation | Important | 6.8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-28898 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 6.3 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-28903 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 6.7 | Pete Batard |

| CVE-2024-28919 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 6.7 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-28920 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 7.8 | Anonymous |

| CVE-2024-28921 | CWE-693: Protection Mechanism Failure | Important | 6.7 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-28922 | CWE-284: Improper Access Control | Important | 4.1 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-28923 | CWE-190: Integer Overflow or Wraparound | Important | 6.4 | Meir Bloya (Microsoft) |

| CVE-2024-28924 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 6.7 | Zammis Clark |

| CVE-2024-28925 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-29061 | CWE-121: Stack-based Buffer Overflow | Important | 7.8 | Azure Yang |

| CVE-2024-29062 | CWE-367: Time-of-check Time-of-use (TOCTOU) Race Condition | Important | 7.1 | Azure Yang |

Some observations of the above vulnerabilities:

- A malicious .bcd file is referenced in CVE-2024-28898, CVE-2024-26189, and CVE-2024-26240.

- Remote exploitation is possible with CVE-2024-20688, CVE-2024-26180, CVE-2024-26189, CVE-2024-26240, CVE-2024-29062, and CVE-2024-28925 as those CVE entries state: “An authenticated attacker could exploit this vulnerability with LAN access. An unauthorized attacker must wait for a user to initiate a connection.”

- Two of the CVEs (CVE-2024-28897 and CVE-2024-28896) are listed as remote access, stating: “An authenticated attacker could exploit this vulnerability with LAN access.”

- Azure Yang is located in China, so according to the law in that country, he needed to disclose his findings to the Chinese government first.

- Zammis Clark is a security researcher who last year gave a presentation about how Secure Boot is broken in general.

- The other vulnerabilities were discovered by Microsoft’s internal teams. Perhaps they were discovered when investigating the externally reported vulnerabilities.

Scope & Severity

While there may be some exceptions, all supported versions of Windows are affected by the new Secure Boot vulnerabilities. The severity ratings also vary, but keep in mind that Microsoft scored them using the CVSS, and bypassing Secure Boot requires that an attacker already have access to the system, which lowers the scores across the board. Microsoft categorizes the Secure Boot vulnerabilities as “Security Feature Bypass” which, while technically correct, doesn’t tell the whole story. Bypassing Secure Boot provides an attacker with an expanded attack surface, enabling persistence and stealth more so than many other attack vectors. And exploiting these weaknesses is possible with infected payloads: Watch this video to see a demonstration of UEFI malware evading EDR detection and bypassing Windows security features.

Eclypsium researchers have presented on Secure Boot dating as far back as 2013 at Black Hat USA in a talk titled A Tale of One Software Bypass of Windows 8 Secure Boot and again in 2014 at Defcon in Summary of Attacks Against BIOS and Secure Boot.

In July 2020 Eclypsium researchers published a vulnerability in the GRUB2 bootloader used by Linux systems dubbed Boothole, and in 2022 published research One Bootloader To Rule Them All in which more Secure Boot bypasses were disclosed, and just this year we disclosed UEFI and Secure Boot vulnerabilities on a line of rugged laptops: Protecting Rugged Gear From UEFI Threats and Secure Boot Vulnerabilities.

At this time there is no evidence that these vulnerabilities are being exploited in the wild. For all 24 of the new Secure Boot vulnerabilities, you must apply the April 9 patches in order to remediate the issues. However, you also need to take additional steps in order to fully remediate—patches alone aren’t enough in this case! Check out this KB article for step-by-step instructions. Keep in mind that if Secure Boot does halt the boot process you will need to go into the UEFI configuration (“BIOS”) and disable it until issues can be remediated. If you’ve set a BIOS password, make sure you know it and test accessing the BIOS first because if you lose access to the BIOS and Secure Boot is halting the boot process you could lock yourself out of the system and have to rebuild.

How Eclypsium Can Help

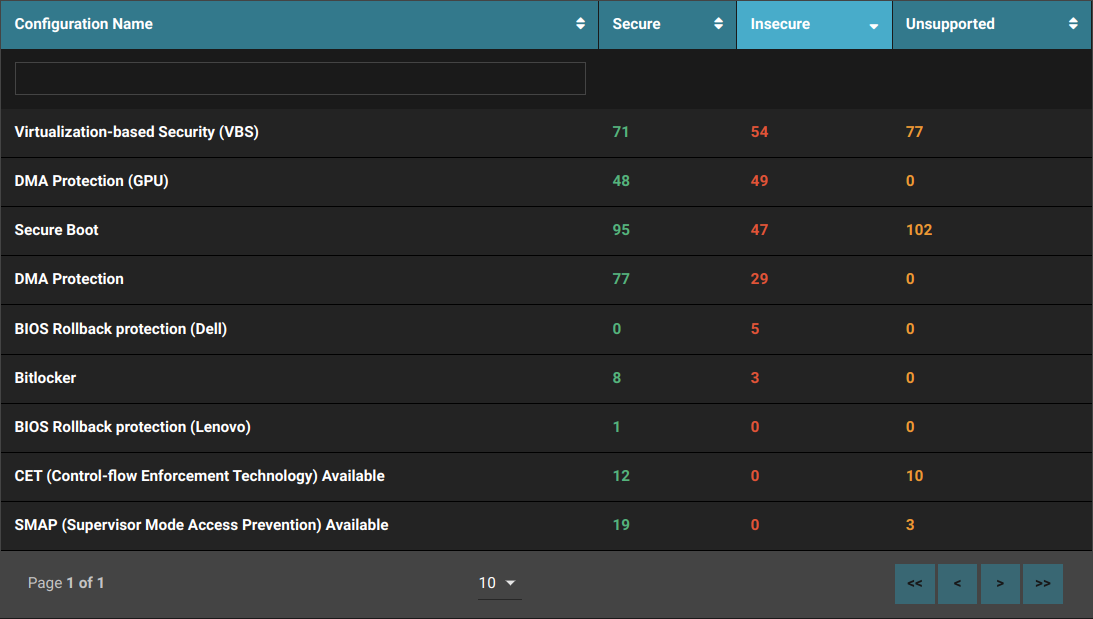

Checking The Secure Boot State: The Eclypsium supply chain security platform provides checks for Secure Boot and indicates if it is enabled/disabled and if the DBX is out-of-date. Also, attackers don’t need to bypass a feature that is already disabled! Make sure you enable Secure Boot on all systems that support it.

Vulnerabilities and Patch Deployment: Our platform identifies a number of different vulnerabilities, including several related to Secure Boot, and allows you to deploy firmware updates on select platforms.

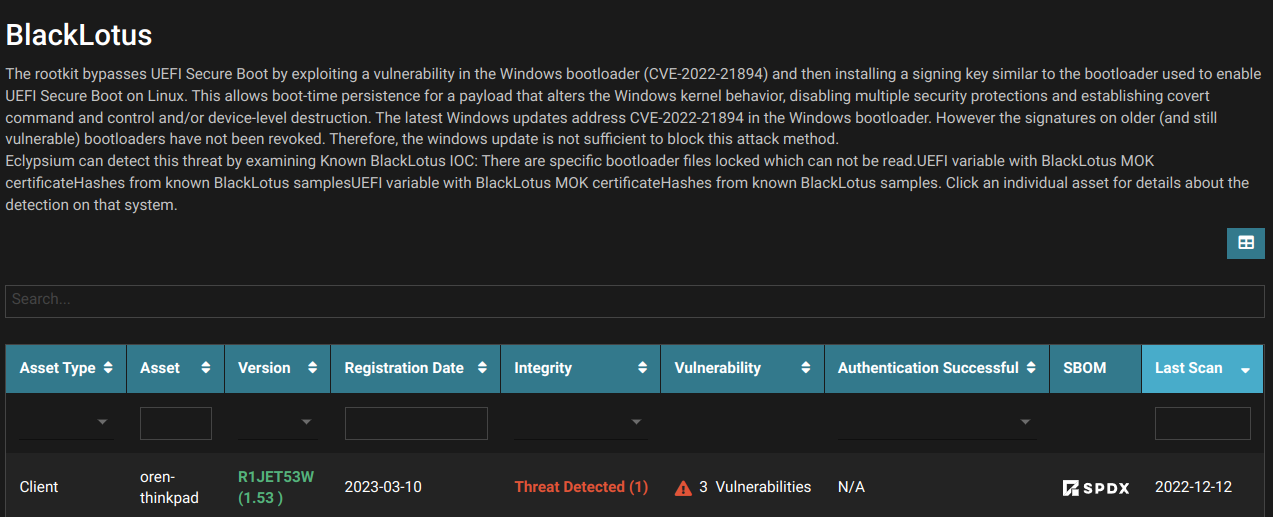

UEFI Threats: We also detect malicious activity in firmware and bootloaders, such as the BlackLotus UEFI malware that can take advantage of these types of vulnerabilities.